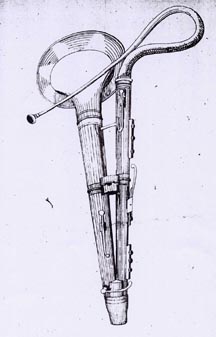

Instruments: English Bass Horn

l-r: German-made English bass horn, English-made English bass horn

The English bass horn (corno di basso; corno inglesa di basso) is now thought to have been invented in 1799 by Louis Alexandre Frichot, a highly regarded, French serpentist who at the time was living in England. This upright serpent with its V-shape, flaring bell and swan-shaped bocal, six chimney fingerholes placed upon the bocal column has three-to-four keys and was typically made of metal (copper and brass). The instrument appeared in British and German military bands as well as within orchestral and harmoniemusik-chamber music ensembles. A 1799 advertisement describes the horn as producing a powerful sound with clearness of tone far superior to the serpent. The English bass horn is distinct from the basse-trompette, another type of upright serpent patented by Frichot in 1810.

The English bass horn is often identified by name in scores and was a particular favorite of Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy. First seeing the instrument in 1824 while on holiday in Northern Germany, Mendelssohn sketched the English bass horn in a letter to his sister and subsequently scored the instrument in his Ouverture fur Vollstande Harmonie-Musik (1824), Harmonie marches for Dusseldorf harmonie (1833-4), Trauer-Marsch (1836) and, most notably, in his overture to Ein Sommernachtstraum (1826) where the English bass horn is aligned with one of the comedic characters in the play, suggesting its ability to obtain a more boisterous, rough tone quality in contrast to Mendelssohn’s earlier description of the instrument having a deep, beautiful sound. The English bass horn is identified by name in other scores across the Continent, from Domenico Briscoli’s 1810 The Conversation of Five Nations grand overtures to Ludwig Spohr’s 1815 Notturno fur Harmonie- und Janitscharenmusik. As was common with most bass horns, the instrument appeared in ensembles and orchestras determined not necessarily by scoring but according often to the availability of players.

to download

a high density image

Please include the following photo credit in any public presentation:

© Craig Kridel,

Berlioz Historical Brass

It should be noted that English-made and German-made English bass horns included similar features; however the placement of the tone-holes on the instruments were differentiated not just according to linear alignment on the air-column but also according to the orientation of the instrument. The chimney fingerholes for the English-made English bass horns were placed on the bocal column 180 degrees from the bell column. In contrast (in what is a more lateral configuration), many German-made English bass horns’ fingerholes were placed 90 degrees from the bell column. In addition to the examples of English bass horns used in Britain, Ireland, and Germany, Moravian communities in the United States used German-made English bass horns for specifically designated parts in anthems. English bass horn makers included William Sandbach and Christian Friedrich Sattler.

The characteristic sound of the bass horn is now difficult to ascertain since the provenance of mouthpieces is so questionable and since the design of the cup and throat shape varies so dramatically. The result is that historically-ascribed bass horn mouthpieces vary considerably according to the sharpness of the throat which, by definition, significantly alters the sound of the instrument. A designated English bass horn mouthpiece in the University of Edinburgh collection, a sharp-throated mouthpiece, similar to serpent mouthpiece designs of the 18th century, produces a soft and more breathy or “reedy” edge to the sound.

to download

a high density image

Please include the following photo credit in any public presentation:

© Craig Kridel,

Berlioz Historical Brass

"The origins of the English bass horn lie in a period of increasing revolutionary activity, when some were straightening the serpent and others were fighting for the Rights of Man." The Tuba Family by Clifford Bevan, 2000, p. 86.

go to the Fall 2016 issue of the ITEA Journal:

"The Dawn of Exploration for the English Bass Horn?" by Craig Kridel [44:1, 28-33]

Serpents and bass horns co-existed during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and the bass horn should not be viewed as a successful or unsuccessful effort to displace the military serpent. Two English bass hornists, Hattersley of Sheffield and Tricket of Scarbrough, performed in the orchestra of the 1823 York Festival, doubling the bass line along with two serpentists. Much of the English bass horn’s military-harmoniemusik role was to blend and engulf the bass sound that combined brass with reed instruments. Too often today bass horns are discredited for their weak intonation, lack of dexterity and, when heard alone, atypical tone quality. In fact, acoustical blending may have been the instrument’s greatest ability and most important feature.

text by Craig Kridel

For a complete description of the different types of bass horns, see

Bass horns and Russian bassoons by Craig Kridel

early 19th century brass

Piccolo Press : ITEA Historical Instrument Section : The Tigers Shout Band : Harmoniemusik : Links