Friends of Berlioz Historical Brass

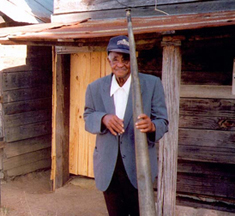

Jeffrey Yelverton, 2019

Selecting the new trumpeter

at Shady Grove Campground

for the October 27, 2019 service

Beginning in 1991 when I first met Shell Johnson, I have helped to provide trumpets for Shady Grove Campground and assisted trumpeters, Mr. Johnson and William Lee Bowman, with the maintenance of their instruments. With the passing of Mr. Bowman in December 2018 and with the guidance of Mr. Jerome Jones of the Board of Trustees, I volunteered to assist the campground elders in their search for a new trumpeter. I am pleased to say that for the October 27, 2019 "Big Sunday" service, Jeffrey Yelverton, a graduate student in music history at the University of South Carolina and U.S Army Bandsmen with the 209th Army Band, agreed to fulfill this role until a permanent trumpeter could be found from the Shady Grove Campground congregation.

An unbroken tradition of horn-blowing has existed at Shady Grove Campground since its formation in the 1870s. With the December 2018 passing of William Bowman, the fifth Shady Grove trumpeter, Shady Grove Campground Trustees are now in the process of selecting the next horn blower.

Shell Johnson, 1991

William Lee Bowman, 2018

Trumpeters of Shady Grove Campground

Caesar Wolfe

Marion Mike Wolfe (son of Caesar)

Richard Wolfe (son of Marion Mike)

Shell Johnson who served from 1959-2007

William Bowman who served from 2008-2018

Jeffrey Yelverton who served in 2019

Gabriel in Black Paradise:

The Trumpet at Shady Grove Campground

by Craig Kridel

Shady Grove Camp Meeting, also known as Black Paradise, is held for one week at the end of October. In recent years, the African American camp meeting has featured the “blowing of the horn” as a ceremonial event to announce the beginning of the culminating “Big Sunday” religious service.

The trumpet holds special meaning at Shady Grove. In 1877, a nearing torrential rainstorm was threatening the ruin of the rice fields of Dorchester farmer S. M. Knight. Knight asked Caesar Wolfe, an ex-slave, to call field hands to help gather the rice crop and, in return, he would give Wolfe and others a six acre brush arbor to be used for religious services. Wolfe, who had learned to play the bugle, blew a horn to call other farm workers to help harvest the crop. Since that day, the sounding of the horn has been a special tradition at Shady Grove.

Since the Shady Grove Campground's founding, five (official) trumpeters have served in the role of “Gabriel”: Caesar Wolfe, Marion Mike Wolfe (son of Caesar), Richard Wolfe (son of Marion Mike), Shell Johnson, and William Bowman (nephew of Shell). During recent years, Shell Johnson (c. 1902-2009) defined this role as “Gabriel at Black Paradise” from 1959 to 2007 and, in 2003, received the Jean Laney Harris Folk Heritage Award of South Carolina. Shell Johnson's nephew, William Lee Bowman (1942-2018), served as trumpeter from 2008-2018. Jeffrey Yelverton served in 2019, and the 2020 and 2021 Shady Grove Camp Meetings were cancelled due to Covid.

The Role of the Trumpet at Camp Meetings

Trumpet calls served different functions at camp meetings as a way to signal the occurrence of events for worshipers in the surrounding area and the more immediate campsites. The horn was used to make the morning wake-up and evening nights-out calls as well as a prayer meeting call and dinner call. In an 1843 account by Robert Carlton of a New York camp meeting, “the worshiper's first full day began when he was 'blasted up by a trumpet call' at daybreak. The second sounding of the horn was the signal for family prayers at each tent or a short prayer meeting around the alter before breakfast.” [Charles A. Johnson, The Frontier Camp Meeting: Religion's Harvest Time. Dallas: Southern Methodist University Press, 1955, p. 123.]

Dickenson Bruce describes similar practices: “About five in the morning after the opening service, a trumpet signaled the time for family prayer in each tent. Following this, another trumpet was sounded, and everyone assembled around the pulpit for morning prayer. The content of this service varied with some accounts reporting only prayer; other, public prayer, sing, and preaching. But by all accounts, the service was brief, ending for breakfast between half-past six and seven.” [And They all Sing Hallelujah: Plain-Folk Camp-Meeting Religion. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1974, p. 81.]

The 1995 Shady Grove Camp Meeting schedule displays many different sermons and devotions throughout the week, each requiring a trumpet signal to call worshipers to events. In addition, specific calls were established for wake-up, dinner, and lights out. These horn calls were reconstructed from my discussions with Shell Johnson and from attendance at camp meetings.

The Construction of Plantation Trumpets at Shady Grove Campground

For an indeterminate number of years, Shell Johnson borrowed the Indian Field Camp Meeting horn in order to blow calls at Shady Grove. In return, he would appear the first week of October during Indian Field's camp meeting and blow trumpet calls. The Indian Field Camp Meeting, established in 1838 and located in St. George, SC, quite near to Shady Grove Campground, is a week-long meeting held by traditionally white Methodist and Baptist churches. [An article about Indian Field Campground, published in the Sept. 22, 1932 Dorchester County Record, makes references to an elderly, African American “tooter, with his seven-foot trumpet, blows a long sonorous blast, it will be the signal for the opening service.” One assumes the trumpeter was either Marion Mike Wolfe or Richard Wolfe.]

In 1991, I met Shell and learned that he did not own his own horn (although he did have a semblance of an instrument—a heavy, somewhat non-playing horn that was fabricated from a roof gutter). The deacon of the Indian Field Campground kindly permitted me to examine and measure their straight trumpet in 1992. I was able to determine that the trumpet was a reed organ (conical) pipe with an integrated trombone-sized mouthpiece. I proceeded to obtain six reed organ pipes and commissioned Professor Michael Swinger, an art historian at Columbus (Ohio) College of Art and Design and builder of portative organs and medieval slide trumpets, to adapt the pipes into six “Black Pardise trumpets” during the summer of 1993. The inner bore of the most resonant sounding instrument was painted red (in the Burgundian horn tradition). The trumpets were taken to Shady Grove Campground during the October 1993 camp meeting where Shell Johnson tried each instrument throughout the week. All six trumpets were used in their traditional setting—to sound calls at Black Paradise.

Michael Swinger and Black Paradise trumpets

At the end of the week, Shell Johnson selected his instrument of choice (the red-bore trumpet), and the remaining “now authentic” plantation trumpets were either held for future used by Shell or subsequently donated to musical instrument collections: The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (Washington, DC); the Horniman Museum (London); the Musical Instrument Collection, University of Edinburgh; the Joe R. & Joella F. Utley Collection of Brass Instruments, National Music Museum (Vermillion, SD); and the Sigal Music Museum (Greenville, SC).

Steven Koivisto and the ornamented Shady Grove trumpet

In 2009, University of South Carolina instrument technician Steven Koivisto of Columbia, SC constructed the ornamented Shady Grove trumpet. This instrument, subsequently shortened so that it may be held solely by the trumpeter, has become the primary horn used at the camp meeting since 2009 along with an adapted Black Paradise trumpet.

Determining the Name of the Shady Grove Horn

No uniform or predefined nomenclature for campground horns exists. While I often heard the instrument referred to as a “horn” at Shady Grove campground, Shell Johnson told me that he preferred the term “trumpet” since he envisioned his role similar to Gabriel's. I mentioned that there were many different types of trumpets, and the horn's unique role deserved a special descriptor. Shell mentioned “field trumpet”; however, I felt that term was reserved more for Western European military instruments. As we talked, he said that the horn blowing went back years before the establishment of the campground, certainly to the plantation era of South Carolina, however one may define that time period. Details of the provenance of the horns or the origins of the practice remain unconfirmed (I suspect the early horns were conventional bugles). I suggested that we call the instrument a "plantation trumpet" since the first trumpeter, Caesar Wolfe, owned a horn before the origins of Shady Grove and, as a former slave, one must assume he had use his horn for calls at a plantation. Shell liked that name for the instrument, and I have introduced this idiosyncratic term to represent these long straight-trumpets.

Camp Meetings in the South

Camp meetings on the southern frontier were said to have originated in the late eighteenth century. While many denominations used such gatherings as a way to draw crowds for the establishment of permanent congregations, after 1805 the majority of meetings were staged by the Methodist Church and became an important aspect of religious practice through the mid-nineteenth century. By 1876, 120 encampments had been established throughout the United States; among these was the Shady Grove Campground for black worshipers, established in the 1870s, and the Indian Field Campground for white worshipers, established in 1838.

The camp meeting activities and practices varied greatly but, in the broadest sense, the gatherings served as a forum for proclamation, revival, political action, family camping and, as epitomized by the Chautauqua model, as a form of religious and general education. As was the case for most outdoor meetings of Methodists in Georgia and the Carolinas (and at Shady Grove), proclamation and revival were highlighted to the virtual exclusion of the celebration of the sacraments. Yet, activities at Shady Grove, while not necessarily sacramental, are certainly viewed as occurring at the “sacred grove.”

While the demeanor of camp meetings suggested piety, in many respects camp meetings were the largest festivals that some rural southerners would ever attend. Towns and rural areas were often vacant during camp meetings, and encampments were attended by those outside the Christian community as well as from other Protestant denominations. While sermons and proclamations were the intent for such gatherings, the primary social event of each meeting was the dinner on the grounds and, specifically, the Sunday dinner culminating the week-long activity—Big Sunday. Women prepared their finest meals in massive quantities; unspoken yet widely recognized competition raged among devoted church members. One timeless account from South Carolina states, “housewives baked and cooked and fried, and piled the tables under the trees high with lordly food—ham and fried chicken, cakes and pie, hidden among mountains of light break and beaten biscuit.” [Ted Ownby, Subduing Satan: Religion, Recreation, and Manhood in the Rural South, 1865-1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990, p. 147.]

Material for this exhibition has been drawn from “Gabriel in Black Paradise” by Craig Kridel in New Directions in Historical Brass Research, edited by S. Carter, (New York: Pendragon Press, 1998), pp. 263-270.

“The campgrounds are truly a mystical place. They are set aside from everyday life so that attendees have time to reflect on how good God has been to them. That happens in heightened moments of worship, when we clap our hands and stomp our feet more expressively than we might in a modern, air-conditioned church. It happens at peaceful moments too, just sitting on a porch looking up through the branches of a tall oak tree. People talk about heaven, but on the grounds you really feel that there is not much space between you and the sky.”

Minuette Floyd, A Place to Worship: African American Camp Meetings in the Carolinas (Columbia: UofSCPress, 2018, p. 10).

Home

: About : Music & Recordings : Performances : Players

: Repertoire : Instruments : Contact

Piccolo Press : ITEA Historical

Instrument Section : The Tigers Shout Band

: Harmoniemusik : Links

exploring the role of early 19th century brass